Malawi is a landlocked country mainly dependent on agricultural exports like tobacco and tea for revenue. 70.1% of Malawi’s population lives below USD 2.15 a day, making it one of the poorest countries in the world. Climate events such as flooding, drought and cyclones have devastated the agricultural sector – the main lifeline for both citizens and the government. The Constitution of the Republic of Malawi provides for the progressive implementation of healthcare for all, commensurate with needs. Many people in Malawi, however, do not enjoy the right to adequate healthcare – those most affected are the poor and vulnerable living in rural areas. The country’s indebtedness, poor budget management, corruption, reliance on donor funding, and exposure to severe climate disasters mean that the government is unable to ensure that people in Malawi can access the right to health, as committed to in the sustainable development goals, the Constitution, the Abuja declaration and several other legal, policy and regulatory proclamations., including the ratification of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1993) and signature of the Africa Charter on Human and People’s Rights (1990).

The story of debt in Malawi

In 2000, Malawi qualified for debt cancellation and restructuring under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative. The country, however, only completed this process and received relief in 2006. Simultaneously it obtained further relief through the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (started in 2005). These interventions reduced debt from over 100% of GDP to less than 20%. Vulnerability to external shocks, Covid-19 and climate events, however, meant debt grew to 66% by 2022.

Most of the country’s debt is owed to foreign creditors, but since the 2013 ‘cashgate’ corruption scandal, both aid and external financing has declined, pushing domestic borrowing upwards. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank classify Malawi as currently being in debt distress and public debt is believed to be unsustainable. In November 2022 Malawi received USD 88.3 million in funding from the IMF to supplement resources for food security. The country has been placed under a 12-month staff-monitored program (IMF) aimed at reducing corruption, enhancing revenue, and improving expenditure. Conditions of accessing additional funding include:

- reducing expenditure while protecting health, education, and social transfers;

- merging existing agricultural subsidies into the unconditional social cash transfer programme;

- freezing public sector hiring barring essential services in health and education;

- restructuring debt under an appointed debt advisor;

- reforming the central bank’s mandate to address inflation and currency volatility;

- enhancing governance and reducing corruption to restore donor and creditor confidence;

- implementing new financial management and tax systems; and revising taxation, including preferential, excise, and small business taxes.

The above conditions may not seem very onerous, but for Malawi, with limited capacity, and unending challenges in resource management, they may well be. For a government to improve capacity and capability, they require dedicated technical assistance and resources – over and above the day-to-day running of the country.

The right to Adequate healthcare in Malawi

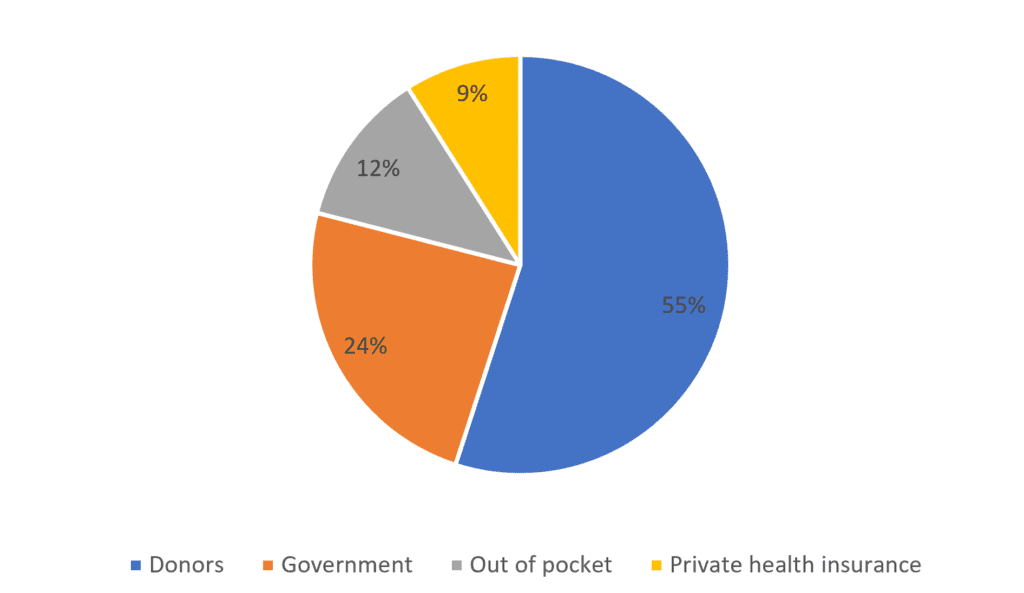

In 2022, health expenditure was 8.8% of government’s budget – well below the Abuja Declaration of 15%. The figure shows that more than half of total health expenditure is made up of aid, meaning government has limited control in expenditure decisions and is vulnerable to the vagaries of international aid politics. Additionally, with 89% of the population employed in the informal economy, many are excluded from private medical insurance, with a significant proportion of out-of-pocket expenditure exacerbating the poverty gap. Primary health care services are insufficient to meet need with many secondary and tertiary level health facilities being relied upon to provide these services. High inflation (15.9% average 2012 – 2020) and the reliance on donor funding makes financing for health unpredictable.

Total health expenditure, 2022

The Covid-19 pandemic showed that planning, budgeting, and spending execution in health emergencies is lacking. Given the history of drought and flooding in the country, this is worrisome. Corruption also plagues the health sector. In the past, funds have allegedly been misused in the handling of medicines, and vulnerable citizens have been put at risk by being forced to make informal payments to receive treatment. Following the “cashgate” scandal in 2013, there was a significant reduction in donor funds. In 2020 and 2021, however, donors stepped up to provide 80% of emergency funding in response to Covid-19, but further corruption and the disappearance of some of these funds has meant government is working hard to rebuild trust.

In January 2023, Malawi published the latest Health Financing Strategy Plan (HFSP III) (2023 – 2030). It is based on commitments made by the country globally, regionally, and locally and aims to achieve universal health coverage. Despite the sizable contribution of aid to health financing, there remains a funding gap of over 50% of total costs. This is not helped by the 32.2% of the health budget lost to global tax abuse (mostly by multinationals), annually. Its inability to generate sufficient revenues puts it in a vicious cycle of dependency on donor aid and loans. The HFSP III provides an extensive explanation of the challenges currently faced in the health sector and the changes envisaged – but remains unproven in tackling these challenges effectively. In the interim, people must rely on their own limited incomes, donors, and humanitarian initiatives to address their unmet health needs arising from poor planning, emergency situations and natural disaster fallouts.

Conclusion

An unfortunate paradox in Malawi is the dissonance between the constitutional promise of healthcare for all and the harsh reality. The fallout of instances of corruption and the pressures of inflation and rising debt has had a crippling effect on healthcare access. And with limited opportunity to significantly increase government tax revenue, Malawi is likely to remain a low-income country for the foreseeable future. The country, however, can strengthen its resource management by preventing and combating corruption; reviewing its tax incentives and tax treaties to ensure revenues are not unnecessarily foregone; reducing its debt burden, in consultation with creditors, to ensure funds are not diverted from providing available, accessible, acceptable, and quality healthcare; and improving the efficiency and effectiveness of spending.