Joshua Franco (@joshyrama) is a Researcher/Advisor on Technology and Human Rights

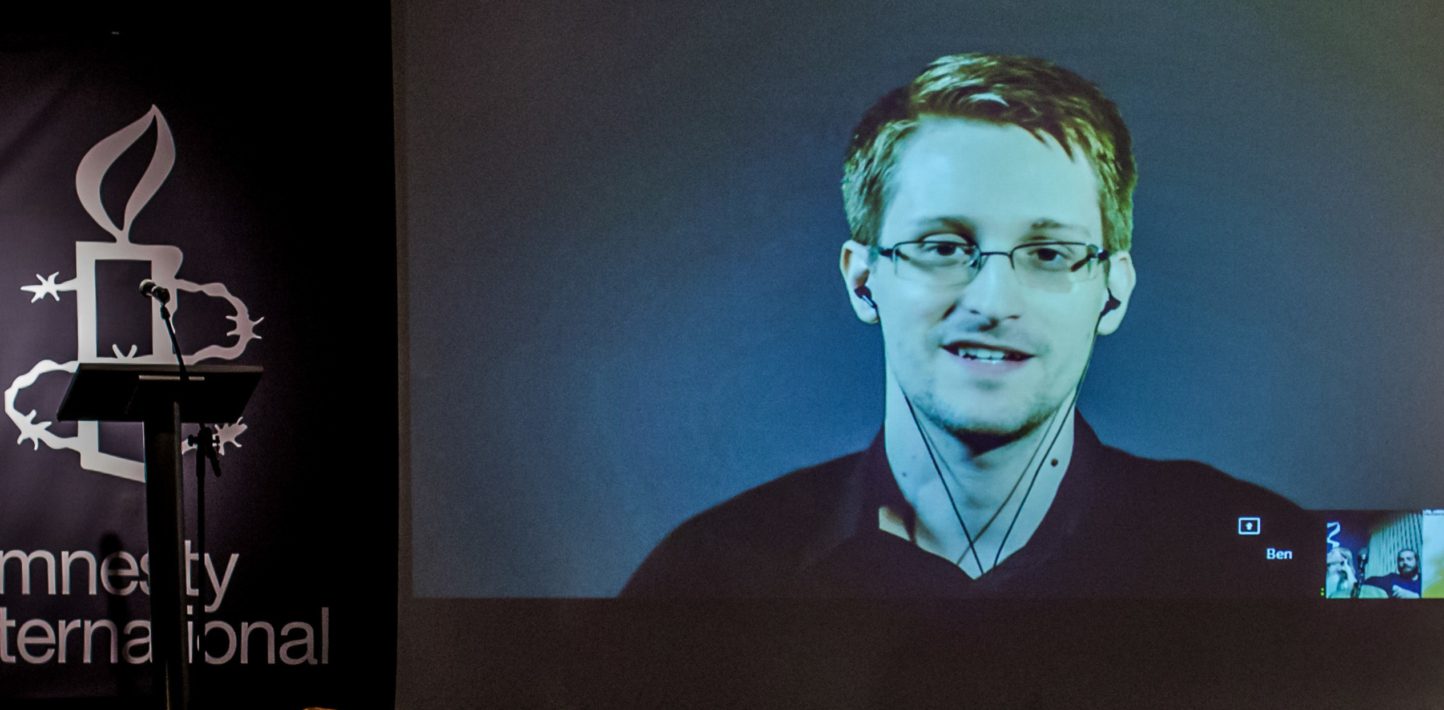

Three years ago, when Edward Snowden was first revealed to be the source of news reports about unlawful mass surveillance programs by the US government, he said, “I don’t want public attention because I don’t want the story to be about me. I want it to be about what the US government is doing.”

Now, three years later, in the midst of a campaign by the ACLU, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and others to pardon Snowden, that risk appears to be greater than ever. A recent editorial by the Washington Post (and at least one other similar piece by Harvard professor Jack Goldsmith) are arguing against a pardon for Snowden. In doing so, they risk dangerously – and incorrectly – minimizing the gravity of the human rights abuses he revealed in an effort to deny a pardon to the whistleblower himself.

These arguments are based on a few flawed premises that need to be corrected.

Premise 1: There is no privacy overseas

The arguments are based on the premise that people outside the USA have no privacy rights. This is wrong.

The Washington Post distinguishes programs such as the cell phone metadata collection program under Section 215 of the PATRIOT ACT (which it grudgingly admits may have raised privacy concerns) and “overseas” programs such as PRISM, which it contends are “clearly legal, and not clearly threatening to privacy.”

Goldsmith likewise cites approvingly the idea that: “The problem is [Snowden] disclosed vastly more than [Section 215 surveillance], involving foreign intelligence not of Americans but of individuals who aren’t American citizens in other countries. No changes were generally made in those programs and Americans don’t really care.” Indeed, Goldsmith seems to believe there is a clear distinction to be made between domestic spying programs, which he concedes were in need of reform and greater transparency, and overseas spying, which he repeatedly states are “obviously lawful.”

For the rest of the world, where opposition to US spying is widespread, this is a difficult premise to accept. Even if these programs are “obviously lawful” under US law (a proposition that is hard to square with ongoing litigation), that says nothing about the question of whether US law comports with its international legal obligations. Nowhere in the numerous international human rights treaties to which the United States is party is there a get-out clause saying that a state’s human rights obligations end at their physical borders. As the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Counter-Terrorism have noted, states have an obligation to respect human rights in their surveillance operations overseas as well as at home. If that argument seems far-fetched to you, think how you would feel about foreign governments scooping up all of your personal communications.

Premise 2: “Overseas” surveillance does not affect Americans

The Post and Prof. Goldsmith believe “overseas” surveillance does not affect Americans. This is also incorrect.

Professor Goldsmith expresses bafflement at how the US Constitution could justify revelations of overseas spying. For example, he asks – presumably rhetorically – “why did [Snowden’s] oath to the Constitution justify disclosure that NSA had developed MonsterMind, a program to respond to cyberattacks automatically [?]” It is odd that he did not see fit to acknowledge Snowden’s answer to this question: “[MonsterMind] means violating the Fourth Amendment, seizing private communications without a warrant, without probable cause or even a suspicion of wrongdoing. For everyone, all the time.”

Without discussing the technical details of all the programs Snowden revealed, or those which Goldsmith cites, I think this response merits some reflection. It illustrates how, given the global and interconnected nature of the internet, there simply is no way to separate domestic and overseas spying in many cases.

It is comforting for people to believe that the Section 215 cell phone metadata program was the only NSA program affecting Americans, and that the other programs affect “only” the rest of the world, but even if this distinction were legally decisive, it is simply not true.

Consider section 702 of the FISA Amendment Act, the law used to justify mass surveillance programs such as PRISM and UPSTREAM that collect massive amounts of data from private company servers and fiber optic cables. These programs are not “targeted” in any meaningful sense – allowing tens of thousands of targets under a single order – and also impact Americans. As the Brennan Center for Justice has pointed out:

“The [US] administration routinely asserts that Section 702 of FISA targets only foreigners overseas. These statements create a false impression that only foreigners’ communications are sought or acquired. In fact, anyone who talks to or about a target is subject to surveillance.”

Moreover, the many – and largely unknown – programs authorized under Executive Order 12333 – also meant to be used only abroad – likely have massive impacts on Americans’ privacy.

Some of this is because the law allows collection of some types of information about Americans under these programs, but it is also due to the nature of the internet. When you log into a website that routes through foreign countries, when you store your information in “cloud” services that may be overseas, you may be subject to the surveillance of these “overseas” communications even without leaving your couch in the middle of the USA. In this interconnected world, it is just not possible to do mass surveillance in a way that leaves Americans unaffected.

Premise 3: A public interest defense would be a blank check for leakers

Those who argue that Snowden should come home to answer for his deeds in court tend to downplay the significance of the fact that the US Espionage Act contains no public interest defense. In other words, the question of whether the leaks were justified as revealing human rights abuses is simply immaterial to whether a leaker spends decades in prison or not. Given the cruel treatment meted out against Chelsea Manning, this omission in law all but guarantees that those who know of government wrongdoing are very unlikely to come forward about it.

The Washington Post admits this legal shortcoming but argue against a public interest defense by saying that “it’s not clear how the law could allow that without creating a huge loophole for leakers.”

This argument again betrays a lack of curiosity about the legal world beyond U.S. borders. Indeed, several countries allow this very defense, and many more require a showing of harm to justify penalizing whistleblowers in the first place, seemingly without disastrous consequences for their national security. And if further clarity is needed, the Washington Post could do worse than to consult the Tshwane Principles on National Security and the Right to Information, drafted after a global consultation that included government representatives, and which explicitly lay out the terms for a public interest defense. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe endorsed the Tshwane Principles after considering whistleblower protections in relation to the Snowden case.

Both the Washington Post and Professor Goldsmith devote a good deal of space to arguing that the harm Snowden’s revelations did to national security was significant, and that he should thus not be pardoned. But the public interest defense is not about arguing that a leak did no harm, but rather that it could be outweighed by its good.

And this belies the very problem with the lack of whistleblower protections in US law. The Post and Goldsmith base their opposition to a pardon on their own assessment of the relative harm and benefit of Snowden’s leaks, but this is exactly the debate that a US court would not be allowed to have. Good faith revelations of human rights abuses should not lead to prosecution, but if they do, it is essential that this defense be available. In its absence, we are left having to depend on the government’s argument of “trust us, but we can’t show you any evidence.” Some people may instinctively want to trust the government on this, but if Snowden’s leaks have taught us anything, it should be that we need to be able to verify the government’s claims.