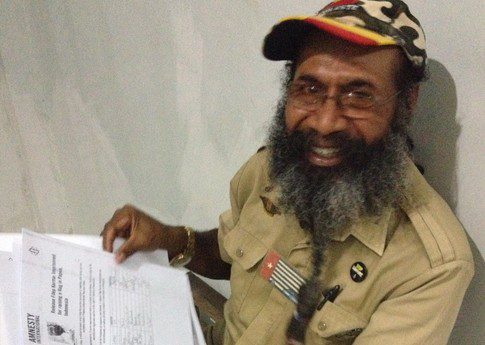

Amnesty supporters worldwide wrote thousands of letters on behalf of Filep Karma who was released from prison in November 2015. Today, he shares why he won’t stop fighting for freedom of expression in Indonesia.

I was born in Jayapura, Papua, the easternmost region of Indonesia. Since my childhood, I witnessed numerous human rights violations.

Under former President Suharto (1966-1998), people who spoke out for the rights of Papuans were immediately accused of separatism by the military government. Anyone who wanted to fight against this injustice had to go [into hiding].

When Papuans demand independence it’s because many of them know that the 1969 independence referendum was unfair. During that time Papuan people were intimidated and coerced by the Indonesian military forces. People were killed or they disappeared. Papuans lived in terror and didn’t have the courage to speak out. I could not accept this.

When I was a civil servant in the 1990s I was invited to study for a year in the Philippines. I learned about Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King – how you could struggle against injustice using peaceful methods. I then decided that Papuans should do the same, and speak up for their rights peacefully.

We have to free ourselves from fear before we can speak out for others.

Filep Karma

Imprisoned for the first time

When Suharto resigned in May 1998, I thought this was the moment to initiate a peaceful Papuan independence campaign. I organized a gathering in Biak city and I led the raising of the Morning Star Flag [a symbol of Papuan independence which is banned in Indonesia].

For this, I was convicted of “treason” and sentenced to six and a half years in prison [the sentence was overturned on appeal after 10 months].

While in detention I received death threats. One day, I got a dog’s head. In the package there was also a letter saying: “I know your family, I know your activities; I know everything, so stay out of it!”

I was scared. But then I thought, if I want to speak out for other people’s rights I have to liberate myself first. We have to free ourselves from fear before we can speak out for others. So I was honest with my family and my kids. I just said, if anything happens to me, don’t be shocked, don’t give up hope and just live your life as normal.

Released from a second jail-term

In May 2015, the Indonesian government released five Papuan political prisoners after they were pardoned by the president. They also offered this to me, but I rejected it. I did not want to accept clemency. I could only accept “abolition” where they annulled my criminal conviction and rehabilitated my reputation.

On 18 November, a prison official informed me that I would be released in the next hour. I initially refused. I said: “Why do you want to kick me out today? At least I should be given a period of adaptation before being released”. The next day they released me. I was in shock.

Amnesty’s letters gave me spirit, reassurance and hope.

Filep Karma

The fight continues

I’m still going to fight for human rights in Papua, and against all the problems Papuans still face. Day by day, there are more Papuans who dare to speak out about their rights.

In January I visited political activists from Maluku imprisoned in Nusakambangan Island, Central Java. I met with [prisoner of conscience] Johan Teterissa for about an hour but unfortunately our conversation was monitored closely by several prison officials.

They were imprisoned only because they organized a peaceful protest by dancing and waving a flag in front of the President [on 29 June 2007]. They were sentenced to 18 years, 20 years and life imprisonment. For me, it’s very odd because they didn’t pose any threat to the president and it was part of their political expression.

They are being imprisoned in Java which is really far from Maluku. A prisoner should not be imprisoned far from his or her family. These things moved me and I can probably help campaign for them. A few months ago I met with the Minister of Law and Human Rights and he promised to move the Moloccan prisoners back to Ambon, the capital city. He did not say when he would; but he did say it would be “easy”.

The power of letter-writing

While I was in prison, I received lots of letters – from elementary, high school and university students, as well as university lecturers from many countries in the world. I give huge thanks to friends from Amnesty International from all around the world who campaigned for me.

I also ask Amnesty to continue to support my friends who are still in prison. Those letters had an enormous impact on me. I think the letters gave me spirit, reassurance and hope. They made me feel like I wasn’t alone.

My message to anyone reading this is: give whatever support and energy you can for friends who are being detained for peacefully expressing their aspirations wherever they are. Amnesty needs to tell the stories of these peaceful defenders of humanity, who are treated unjustly and inhumanly, so that people from all around the world know their story.