Patrick recently travelled to Somalia where he interviewed a number of people who had been returned from Kenya after living in Dadaab refugee camp. Names in this blog have been changed to protect the sources.

Ubaax (pronounced as Ubah), originally from Dinsoor district, looked at me, then bent her head as tears rolled down her thin, shiny cheeks. I looked out of the window as I absorbed what she had just said.

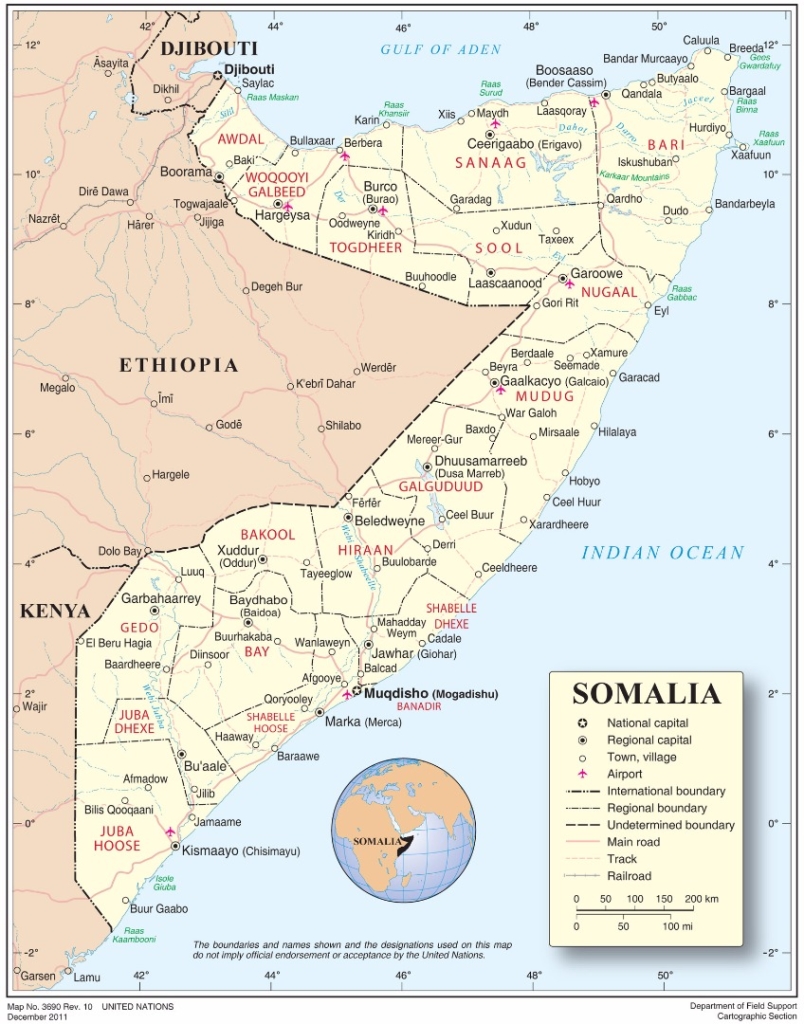

By mid-2011, Ubaax, her husband and their 11 children were facing a desperate dilemma: either wait for famine to kill them in Dinsoor; or walk the long distance to Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya. She chose the latter. But the distance of more than 600 kilometres was too much for her five youngest children.

The thought of anyone walking for 600 kilometres in search of food and dying of hunger along the way is heart-wrenching. That this happened to children under five years of age is devastating.

Patrick Mbugua, Somalia Researcher, Amnesty International

“They died of hunger, cholera and exhaustion from the long walk,” she told me. The thought of anyone walking for 600 kilometres in search of food and dying of hunger along the way is heart-wrenching. That this happened to children under five years of age is devastating.

I interviewed Ubaax on 25 April 2017 in Baidoa town in Somalia. She was among the many Somali refugee returnees that I interviewed in Baidoa and Kismayu towns from 23 April to 4 May 2017. I found their stories emotionally draining. From time-to-time, I would pause to let people who had broken down re-compose themselves.

Ubaax lived in Dadaab for five years and returned to Somalia in August 2016. “We bought a small piece of land with the money the [United Nations High Commission for Refugees] UNHCR gave us. The Norwegian Refugee Council [NRC] came and built us a one-room house where we now live,” she revealed.

Her compatriots in Dadaab included Rashid, a man originally from Bootis in Baidoa, who also walked with his family from Baidoa to Dadaab in 2011. He returned in August 2016 and now lives in Wadajir district where he bought a piece of land with his return money.

Another returnee, originally from Baardhere district in Gedo region, told me that famine and war had displaced him in 2011. “I went to Dadaab after al-Shaabab occupied our area and blocked international food distribution,” he testified. He returned to Baidoa in January 2017. “I chose to return to Baidoa because it was safe for me and my family. We are Rahanweyn; we are safe here.” Rahanweyn is a Somali ethnic group which is a majority group in Baidoa. He lives in one of the internally displaced persons (IDPs) settlement outside Baidoa and does odd jobs to get by.

Another man from the minority Dabare ethnic group fled famine after al-Shaabab took over his area in Dinsoor district and blocked international assistance. He walked with his family for about 100 kilometres and then rode a lorry to Daadab. I asked him why he returned to Baidoa. “Dinsoor is my home, but drought is killing people there,” he answered. Many other returnees originally from Baardhere, Dinsoor, Hodur and other surrounding districts also opted to return to Baidoa.

Asking them about their passage through al-Shaabab controlled areas and road blocks, one woman explained: “The truck drivers know the roads and where al-Shaabab put road blocks.” Typically, when approaching an al-Shaabab road block, travellers see a young man whose head is fully covered with a black and white scarf, standing in the middle of the road pointing a gun towards the oncoming vehicle. “You don’t see the others; the man usually talks to the driver.” The man takes money from the driver and then inspects everybody in the vehicle. He collects all smart phones and destroys any school or college certificates. In some places, she added, passengers don’t see any armed man—the driver just stops by a thicket, tells the passengers the militants are watching them and walks into the bush. The driver returns after a few minutes and proceeds with the journey.

An interviewee from Buaarle district, which al-Shaabab controls, said that the militants tax markets. “They ask for money or take livestock.” I asked him how he fled the area. “I avoided roads and walked for many kilometres through the bushes,” he answered.

Returnees in Baidoa and Kismayu had stories of suffering and pain, and ethnic or clan identity often influenced their choice of return location. Famine was the biggest reason many had originally left Baidoa, while war had originally caused the displacement of those who had fled Kismayu. “I ran to Dadaab in 2009 when al-Shaabab occupied Kismayu,” one man told me. I met some returnees in Kismayu who had fled in the early 1990s and then stayed in Kenya for more than 20 years.

The majority of those that I met in Baidoa returned because Daadab was closing, while the majority of those in Kismayu came back because peace had returned to their home. “I wanted to come back home after staying in Kenya for 25 years,” one returnee revealed.

Interviewing returnees in Baidoa and Kismayu is a nerve-racking experience. They shared personal stories that are haunting and resulted in nightmares many days after the interviews. It is more agonising for the returnees because it often revives painful memories.