Turkish authorities have fired 130,000 people from their jobs the last two years. Most haven’t even been told why.

“Imagine you wake up one day and both you and your wife have been dismissed from your jobs. There is no other job for which you are equipped. You do not know how you will get by. That is the situation my partner and I faced… Nobody [from work] told us anything – we found out everything by looking online.”

The quote above is from Deniz*. On an otherwise ordinary September morning in 2016, Deniz and his wife Elif* received some awful news. Without any warning or reason, they were both dismissed from their jobs as school teachers in Turkey. Panic set in; with no jobs, how would they pay the bills, buy food or take care of their families?

The world turned upside down

Deniz and Elif’s story is sadly all too typical. They are just two of around 130,000 people with public sector jobs who were summarily dismissed by a series of executive decrees during Turkey’s two-year state of emergency. The state of emergency, which was put in place after the attempted coup in 2016, is now over, but for those left without jobs, their ordeal is definitely not.

None of the people who lost their jobs were given a specific reason why they were fired. The only information authorities provided in the emergency decrees on dismissals was that they were dismissed for supposedly having ‘links’ to ‘terrorist’ groups. No further details were given.

At first, Deniz thought he would quickly get his job back, as this was obviously just a terrible misunderstanding. ‘We thought there would be an investigation and that we would be reinstated. My wife was subjected to a criminal investigation [and charges] were all dropped. Yet here we are, still in the same situation two years on.’

No effective remedy

A new report by Amnesty International, Purged Beyond Return? No Remedy for Turkey’s Dismissed Public Sector Workers, examines the systematic failings of the state to let public sector workers seek redress for their arbitrary dismissals. This report builds on the previous research on these mass dismissals and their consequences that was published by Amnesty International in 2017 in No End in Sight: Purged Public Sector Workers Denied a Future in Turkey.

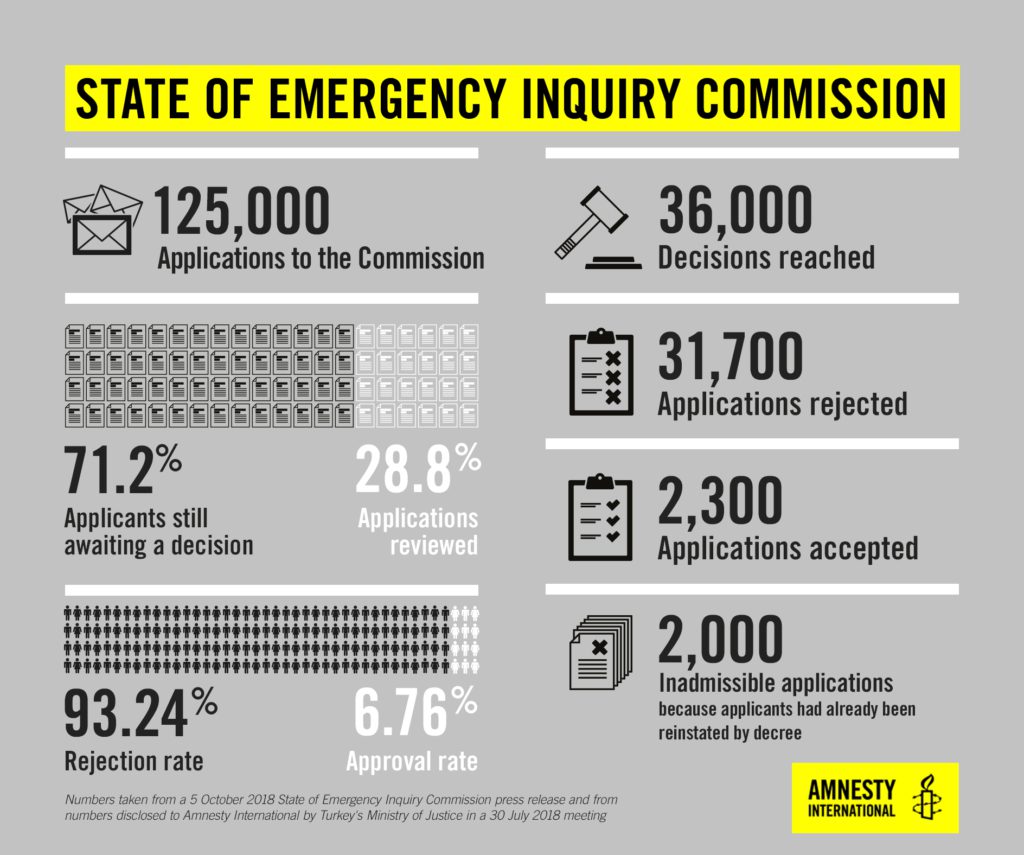

Like tens of thousands of Turkey’s purged public sector workers, Deniz was initially denied the right to appeal the termination of his job. The State of Emergency Inquiry Commission was eventually set up in January 2017 to consider appeals, but only began accepting applications in July 2017, and delivered its first decisions in December 2017 – almost a year and a half after the first people lost their jobs.

Many of the people we spoke to told us of the difficulties they faced when making their applications to the Commission. A Kafkaesque ordeal lay ahead of them: how could they argue against their dismissal without knowing why they were dismissed in the first place? This meant they had to make an appeal in broad terms, or worse, take a guess at why the authorities had decided to terminate their contracts.

Ayşegül*, whose husband Ali* was fired from his job at the state broadcaster TRT, described it succinctly: ‘We made an appeal without knowing what exactly we were appealing against.’

Forcing public sector workers to base their appeals on guesswork is just one of the many failings that we came across during the research for our report. We also found that the Commission lacks genuine institutional independence, uses protracted review procedures, fails to provide applicants with the chance to effectively rebut allegations, and presents participation in everyday lawful activities, such as depositing money in a certain bank or enrolling a child in a certain school, as ‘evidence’ for upholding dismissals.

We also uncovered serious issues affecting those who were restored to their jobs. We found that they receive inadequate compensation packages and face demotion upon reinstatement if they had occupied management positions prior to their dismissals.

It is clear that the Commission cannot provide a meaningful or effective remedy for Turkey’s dismissed public sector workers. Indeed, it seems to exist in order to practically rubber-stamp vast majority of the dismissals, rather than rigorously scrutinize the merits of each case. In the 15 months since it began accepting applications, the Commission has only reviewed 36,000 out of 125,000 submitted applications. Of the reviewed cases, only 2,300 have resulted in reinstatements.

Ostracization, isolation, depression

Since names of public sector workers dismissed from their jobs are published on lists attached to the executive decrees, the social impact of this public naming and shaming is all too acute.

Deniz describes his experience of feeling like an outcast: ‘People are reluctant to even say hello to you. Your neighbours look at you differently. They pretend not to see you when they walk down the street. While you do not know exactly what you have been accused of, you are labelled as a ‘terrorist’ and left completely isolated, even from those closest to you.’

But it’s not only those who have lost their jobs who face repercussions from the purges. These mass dismissals also gravely affect their families:

“My son is studying engineering at university’ Ayşegül says. ‘He told us that his friends (…) don’t speak to him anymore. At one point he felt like dropping out of university. Such was the disruption of this social stigma to his studies.”

Huge economic cost, untold psychological impact

The financial impact of the mass dismissals has been especially debilitating for many. Permanently banned from employment in the public sector, those dismissed have no alternative but to turn to an unsympathetic private sector, where many employers are reluctant to give jobs to those fired by the authorities.

This financial strain, coupled with the deep social stigma attached to the dismissals, has left many people with serious psychological difficulties. Having been out of work for 16 months, Kerem*, a hospital radiology technician, was able to get his job back earlier this year, after the Commission accepted that he had no links to any terrorist groups. His psychological scars, however, did not go away.

“I was shocked when I found out that I had been dismissed. It was not something that I was expecting. I had done nothing wrong. Seeing my name on that list… was devastating to me and my family. I didn’t leave the house for eight months. I received psychological treatment… I’m still in therapy today. All this happened to me even though I had done nothing wrong.”

“I have two children aged 11 and 5-years-old. They too suffered psychological trauma… The police came and searched the house. They were looking for books, newspapers or documents to incriminate me. They seized my computer. They seized my phone.”

Future? What future?

Turkey’s two-year state of emergency finally came to an end on 18 July 2018, but for tens of thousands of dismissed public sector workers life is still not back to normal. They continue to live with the devastating impact of their very public dismissals.

“We will not return as the people we once used to be”, said Cengiz*, an academic dismissed after signing a petition calling for an end to Turkey’s decades-long conflict with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

“I was essentially publicly branded. I was prevented from pursuing my academic career. I had to get work on construction sites because nobody else would give me a job.”

“One of the most fundamental values a person has is their sense of justice. In Turkey, the justice system is in thrall to the politicians… it changes according to the political climate… The moment you lose the sense that you have [access to] justice, you lose your sense of belonging to a country.”

*Names have been changed to protect the identities of interviewees