First published on LeMonde.fr on 2nd April 2019

Since 22 February, millions of Algerians have taken to the streets in largely peaceful protests against President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s bid to remain in power. Under pressure, the 82-year-old – who has been in power for 20 years – announced on Monday 1st April that he will be resigning before the end of his mandate, on 28 April.

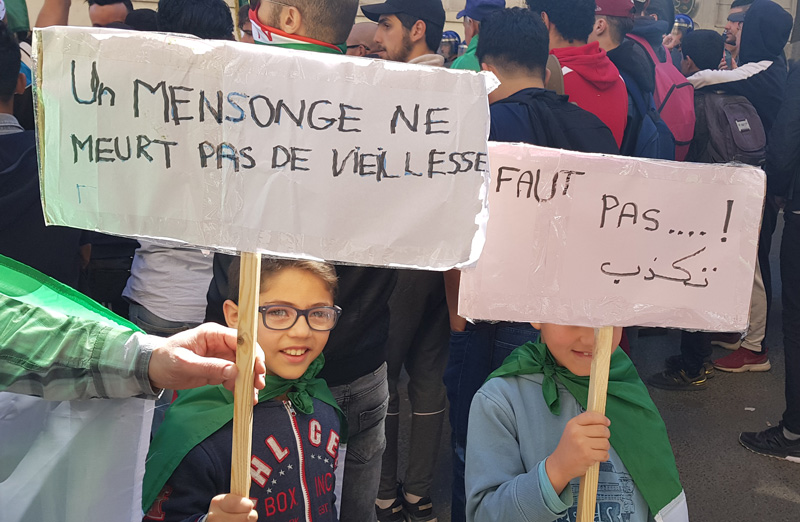

So, meanwhile, the protests – the biggest exercise of freedom of expression and assembly in Algeria in decades – continue.

During my recent two-week mission to Algiers, it was wonderful to feel the strong sense of optimism sweeping the country; and the belief that change is inevitable.

Algerians believe there is nothing that can hold them back from voicing their opposition towards what they callthe “gang of thieves”. Even the authorities appear to have softened their suppression of dissent, by allowing demonstrations to take place in Algiers and elsewhere in Algeria despite a de facto ban on protests in the capital since 2001, and a prohibition on all unauthorized protests.

These are positive developments, but there is still much more to be done to secure positive human rights change in Algeria.

The Algerian state needs to lift all restrictions on the right to peaceful expression and assembly and end the arbitrary arrests of those calling for change. It needs tostopping politically motivated prosecutions, such as the one against the imprisoned activist Hadj Gharmoul who Amnesty International calls to free. It also means tackling injustices linked to a system of hogra, an Algerian expression that is commonly used to describe the state’s abuse and oppression, and the impunity that has gone with it.

Excessive use of force

Even though the protests have taken place in an overwhelmingly positive atmosphere, there have been deeply worrying reports of police using unnecessary or excessive force, firing tear gas and rubber bullets at peaceful protesters, and using water cannons and electrical weapons for crowd control. While the majority of protesters were demonstrating peacefully, some have thrown stones at the police after they began firing teargas.

During my visit, I met a 14-year-old boy who had been injured on 22 March by a rubber bullet fired by police officers. I found him nursing his injury in the stairwell of a building in Algiers. He said he was from the Bab El Oued neighbourhood and had been protesting peacefully every Friday. A tough little guy, he said his injury would not prevent him from coming back to protest for a change of the system.

Dozens of arrests

Amnesty International is also concerned by the number of arrests that have taken place, with at least 311 people detained since the demonstrations began. Some were released after few hours including ten journalists arrested on 28 February while covering or taking part in a protest calling for press freedom. At least 20 protesters are currently on trial on “unarmed gatherings” charges used to criminalize peaceful protests, while others are prosecuted for acts of violence and theft.

I spoke to a family member of one of the people prosecuted after the 15 March protests. He told me his brother was arrested and brought before a judge on 17 March, accused of “unarmed gathering” under Articles 97 of the Algerian Penal Code. The man was released but has to appear before the judge on 23 May; and there are at least 19 others in the same situation.

Almost every week the police reveal that scores of people have been arrested, some of them for “unarmed gathering”. Abdelghani Badi, a lawyer, tells me it is time the Algerian authorities stops “giving with their left hand what they take with their right one” – referring to the prosecutions for “unarmed gatherings”, despite the constitution guaranteeing the right to freedom of assembly.

Some protesters were arbitrarily arrested for a few hours before being released, sometimes at night, several kilometres outside of Algiers. People say that this is supposed to act as a warning to protesters – those who need to “think about their actions”.

On 24 February, Fares Bedhouche was arrested and detained near place Audin in Algiers for more than 12 hours. He believes he was targeted for being an activist from the Jil Jadid (New Generation) political party, a member of the Mouwatana (Citizenship) Collective which called for the initial 24 February protest.

“This is unjustifiable and an attack on my fundamental rights. Even the police officers could not tell why I was being held,” Fares told me. “They were just waiting for a call for me to be released from Tessala El Merdja [a town in Algiers province] police station, more than 25 kilometres away from the place of my arrest at 11.20 pm.”

Fear of future reprisals

Many of the people I spoke to shared their fear of future reprisals, especially against the journalists, judges and lawyers who have voiced their support for the protests or called for media freedom and independence of the judiciary. During my visit, I documented the cases of four individuals – one journalist, two judges and one lawyer – who faced threats or disciplinary action because they expressed their support for the protests or refused to convict protesters based on insufficient evidence.

Foreign journalists are also restricted in their activities. On March 31, Reuters journalist Tarek Amara was deported after being arrested while covering a demonstration against President Bouteflika.

“Algeria has a unique opportunity to usher in a new era of human rights”, Hassina Oussedik, director of Amnesty International Algeria, told me. “Authorities must ensure that fundamental liberties are protected and that every Algerian has access to justice. Those are priorities.”

Let’s hope Algerian authorities show they have heard the millions of voices that are clamouring for change.