WARNING:

This report contains descriptions of violence against women.

Violence and abuse against women on Twitter has become far too common an experience.

Although people of all genders can experience violence and abuse online, the abuse experienced by women is often sexist or misogynistic in nature, and online threats of violence against women are often sexualized and include specific references to women’s bodies. The aim of violence and abuse is to create a hostile online environment for women with the goal of shaming, intimidating, degrading, belittling or silencing women. The women interviewed by Amnesty International have experienced a wide spectrum of violence and abuse on Twitter which have negatively impacted on their human rights.

Abuse on Twitter can include general nastiness or name calling (you b*tch, slut, c*nt). It can be more targeted harassment or can be more direct threats – which in the past I have had directed at my daughter. I’ve had my address, my tax information, as well as my phone number released.

Jessica Valenti, US journalist and writer

What is Violence and Abuse against Women Online?

According to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, discrimination against women includes gender-based violence, that is, “violence which is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately, and, as such, is a violation of their human rights.” The Committee also states that gender-based violence against women includes (but is not limited to) physical, sexual, psychological or economic harm or suffering to women as well as threats of such acts.

International human rights standards emphasize that the concept of ‘violence against women’ is a form of gender-based violence. The UN uses the term ‘gender-based violence against women’ to explicitly recognize the gendered causes and impacts of such violence. The term gender-based violence further strengthens the understanding of such violence as a societal – not individual – problem requiring comprehensive responses. Moreover, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women states that a woman’s right to a live free from gender-based violence is indivisible from, and interdependent on, other human rights, including the rights to freedom of expression, participation, assembly and association.

Violence and abuse against women on social media, including Twitter, includes a variety of experiences such as direct or indirect threats of physical or sexual violence, abuse targeting one or more aspects of a woman’s identity (e.g., racism, transphobia, etc.,), targeted harassment, privacy violations such as doxing – i.e. uploading private identifying information publically with the aim to cause alarm or distress, and the sharing of sexual or intimate images of a woman without her consent. Sometimes one or more forms of such violence and abuse will be used together as part of a coordinated attack against an individual which is often referred to as a ‘pile-on’. Individuals who engage in a pattern of targeted harassment against a person are often called ‘trolls’.

It is important to note that violence and abuse online can take place in many different contexts. In November 2017, Amnesty International commissioned an online poll with Ipsos MORI about women’s experiences of abuse and harassment on social media platforms across eight countries including the USA and UK. The findings showed that nearly a quarter (23%) of the women surveyed across the eight countries said they had experienced online abuse or harassment at least once, including 21% of women polled in the UK and 1/3 (33%) of women polled in the US. In both countries, 59% of women who experienced abuse or harassment said the perpetrators were complete strangers.

Although most of the women interviewed for Amnesty International’s research received violent and abusive tweets from strangers or people unknown to them, online violence and abuse can also be used as a tactic by current or former intimate/domestic partners of women to control t women and instil fear. A survey conducted by the US organization National Network to End Domestic Violence found that ‘97 percent of domestic violence programs reported that abusers use technology to stalk, harass, and control victims’. It also found that 86 percent of domestic violence programs reported that victims are harassed through social media. In the UK, research on domestic online abuse by domestic violence organization Women’s Aid found that 85% of respondents said the abuse they received online from a partner or ex-partner was part of a pattern of abuse they also experienced offline. Additionally, 50% of respondents stated that the online abuse they experienced also involved direct threats to them or someone they knew. Of the women polled by Amnesty International who experienced abuse or harassment on social media platforms, 18% of women in the UK and 23% of women in the US said that the perpetrators of the abuse were current or former partners.

The Many Forms of Violence And Abuse On Twitter

Amnesty International’s online poll found that women have experienced a variety of abuse and harassment on social media platforms, including Twitter. Of the women polled who had experienced abuse or harassment on social media platforms – 29% of women in the USA said they had experienced threats of physical or sexual violence, with 27% experiencing such threats in the UK. Around half of women polled who experienced abuse or harassment said that the abuse included sexist or misogynistic comments (53% in the USA and 47% in the UK).

Threats of Violence

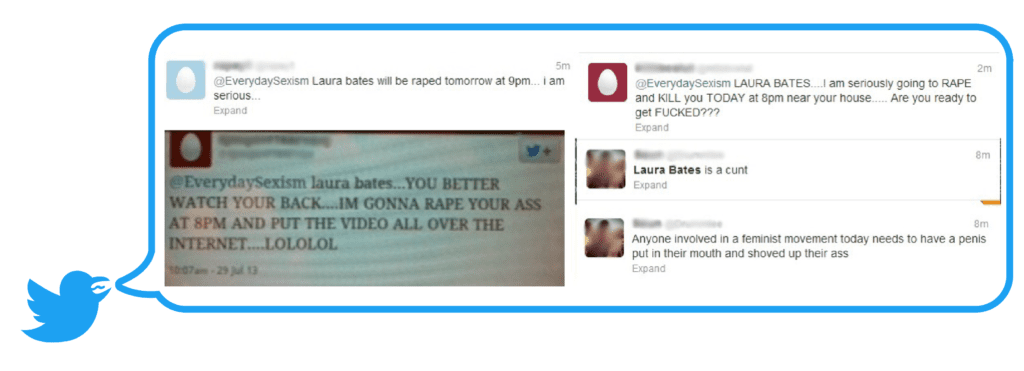

Threats of violence against women online includes both direct and indirect threats that can be physical or sexual in nature. Several women who spoke to Amnesty International about their experience of violence and abuse online reported receiving threats of violence on Twitter. For example, UK women’s rights activist and writer Laura Bates has experienced multiple forms of sexually violent threats against her on Twitter. She told Amnesty,

“Online abuse began for me when I started the Everyday Sexism Project — before it had become particularly high-profile or I received many entries. Even at that stage, it was attracting around 200 abusive messages on the site per day. The abuse then diversified into other forums, such as Facebook and Twitter messages. These often spike if I’ve been in the media… You could be sitting at home in your living room, outside of working hours, and suddenly someone is able to send you a graphic rape threat right into the palm of your hand.”

UK political comedian Kate Smurthwaite told Amnesty International about a pile-on of violence and abuse against her on Twitter following a media appearance on a television debate programme. She told us,

“..After the debate he continued to be rude about me on Twitter. That reached a whole new level. In the following 48 hours, I received 165 pages of Twitter abuse. Suddenly it went insane. In that, there were four or five death threats, rape threats, and things like that.”

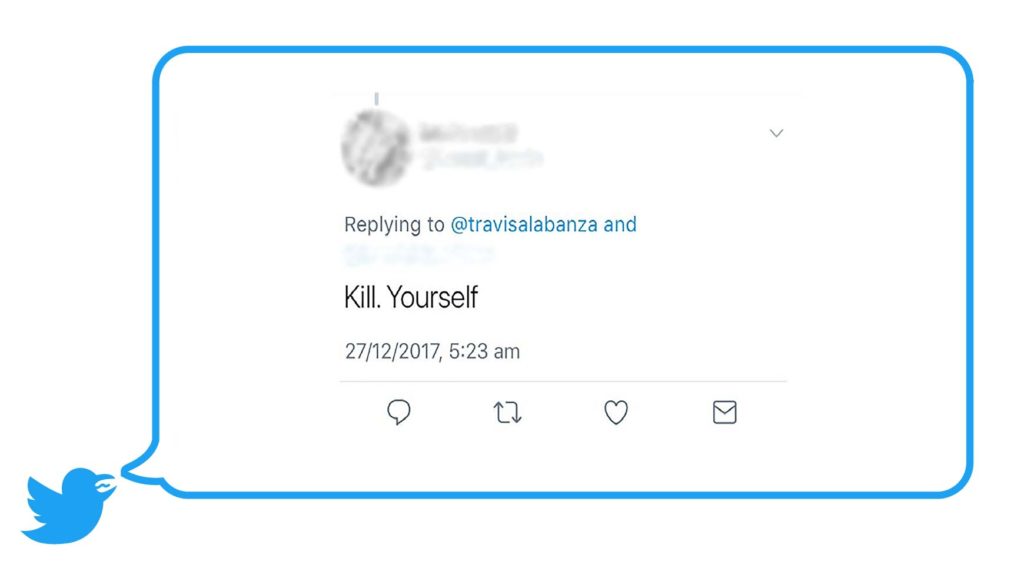

UK poet and actor Travis Alabanza told Amnesty International that much of the violence and abuse they experienced on Twitter was from people telling them to die. Travis explained,

“A lot of it was ‘die’. It was a mix, a lot of ‘I wish you people wouldn’t exist’. ‘Go create your own world’ or ‘set up your own country’. And ‘Die’. ‘Die’. ‘Die’. ‘Die.’ Lots of death.”

UK writer Danielle Dash summed up her experience of violent threats on Twitter. She said,

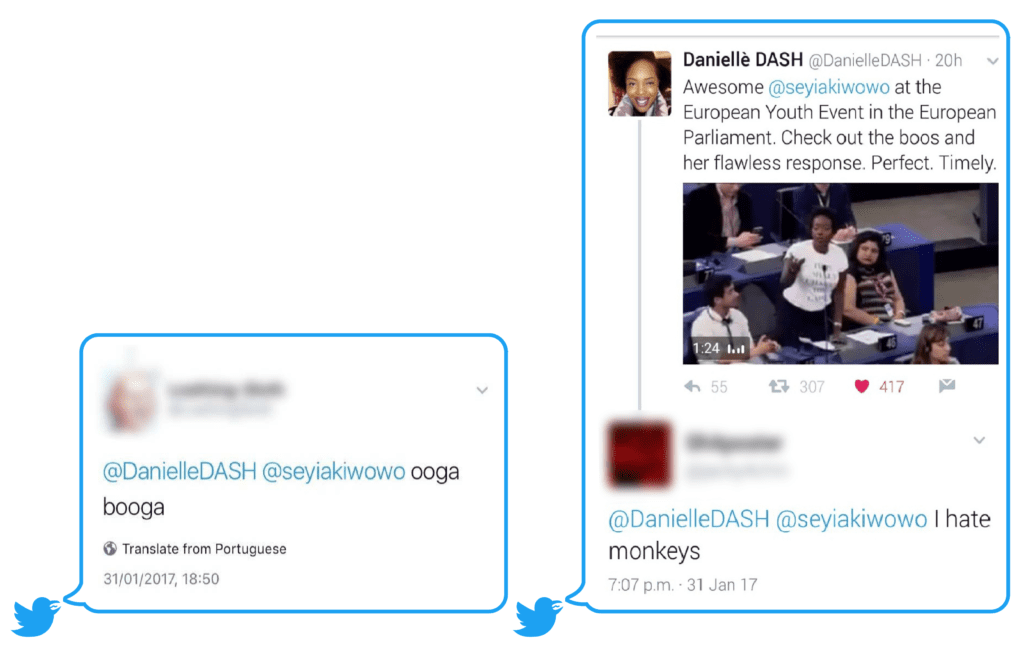

“The violence is at the intersection of everything that I am – for example – ‘I’m going to rape you, you black b*tch’. You have the misogyny, and you have the racism and you have the sexual violence all mixed up into one delicious stew of cesspit shit.”

UK journalist Allison Morris told Amnesty International about threats she has received against herself as well as her family. She stated,

“Some of the things that have been put on Twitter about me have had people say they know where I live, I’ve had people say that they’ll be outside my work, I’ve had people not just threaten me but also say things that, you know, are clearly veiled threats against my family.”

Threats of violence and abuse online can also have a profound impact on women’s sense of safety offline. Amnesty International’s online poll found that of the women who experienced abuse or harassment online, 42% in the USA and 36% in the UK said it made them feel that their physical safety was threatened. 1 in 5 of women in the UK (20%) and over 1 in 4 (26%) in the USA said they felt their family’s safety was at risk after experiencing abuse or harassment on social media platforms.

US reproductive rights activist Pamela Merritt echoed these findings. She said,

“After five years of online harassment coupled with offline harassment, I have basically reconciled with the fact that I’m prepared to die for the work I do. That might happen. If you get 200 death threats, it only takes one person who really wants to kill you.”

US journalist and writer Jessica Valenti told Amnesty International about how difficult it is to assess the seriousness of threats made against her online. She explained,

“When you’re in real life you decipher what is a real threat and what is not. Should I cross to the other side of the street, or should I tell this person to f*ck off? You can make informed decisions in that moment. You can’t do that online because you don’t know where or who that person is. Is this person a real threat or is this person a 12 year old? You have no clue.”

Women who have experienced threats of violence on social media platforms, including Twitter, also told Amnesty International about the precautionary measures they have taken to protect their families from this abuse. One woman told Amnesty that she changed her child’s last name at school so the child could not be identified as someone related to her and targeted with abuse. Another woman told Amnesty International that she turned down media appearances once her pregnancy became visible because she was terrified of any abuse or violence online targeting the baby. Her particular fear of such violence and abuse was triggered by previous threats of sexual violence towards her sister on Twitter.

Sexist and Misogynistic Abuse

Although different levels of abuse on Twitter will require different responses from the platform, Amnesty International’s research has found that all forms of abuse against women can have a harmful impact on women’s rights online. Sexist and misogynistic abuse against women on Twitter was highlighted by almost every woman interviewed by Amnesty International. Such abuse includes offensive, insulting or abusive language or images directed at women on the basis of their gender and is intended to shame, intimidate or degrade women. Sexist or misogynistic abuse often includes references to negative and harmful stereotypes against women and can include gendered profanity.

Politician and Former Leader of the Labour Party in Scotland Kezia Dugdale told Amnesty International about the underlying misogyny in tweets she has received,

“It’s definitely the case that I get more sexist commentary on Twitter and online than men. In Scotland the phrase would be ‘Daft wee lassie complex’. It means she doesn’t know what she’s talking about – she’s too young, too female to really understand what she’s going on about. So people will question your intelligence by referring to your gender. That’s probably the most common theme.”

UK activist Alex Runswick also spoke about the variety of misogynistic abuse she has experienced on Twitter. She recounted a particular wave of abuse she received after she posted a photo of a letter that had assumed she was a man. She said,

“Because my name is Alex, I often get mis-gendered. I took a photo of the letter and put it on Twitter and said ‘Just because I’m a Director does not mean that I am male!’ and used the Everyday Sexism hashtag. And then I got, for me, an enormous amount of abuse for something I didn’t expect to be remotely controversial…It started with straightforward anti-women stuff around ‘you shouldn’t be doing politics’, ‘you should be in the kitchen’, ‘go make me a cup of tea love’…but then it quickly moved into what sort of sex acts I should be performing, my appearance and whether they ‘would or wouldn’t’”

Women also told Amnesty International that they often receive a spike in violence or abuse online following a television or media appearance. For example, UK science broadcaster, writer and educator Dr Emily Grossman told Amnesty International about a barrage of abuse she experienced on Twitter following an appearance in a TV debate. She explained to Amnesty International how she categorized the scale of abuse she received,

“There were personal attacks on me and my appearance, there was sexually abusive and aggressive language – no rape threats or death threats – but certainly people talking about their cock and slapping it around my face, what they wanted to ‘do’ to me, tearing me a new arsehole. Then there were these comments on my qualifications and my career undermining me as a scientist. There was some really awful anti-Semitism saying that Hitler was right…And there was a category of messages that seemed to be attacking me as a representative of all women – saying that women weren’t clever enough to be scientists, that we were stupid, illogical, irrational, if you can’t stand the heat get back in the kitchen, or if women aren’t succeeding blame it on their DNA. And then there were comments saying I must be a feminist and be crazy and asking why I hate men or suggesting that maybe my uncle raped me…”

Other forms of identity-based abuse

Sometimes, online abuse focuses solely on an aspect of a person’s identity other than their gender. Under Under international human rights legal frameworks, the right to non-discrimination covers multiple protected characteristics of a person’s identity including standards to tackle discrimination against women, minorities, racial and religious discrimination and discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.

A 2017 report by LGBT organization Stonewall commissioned by YouGov surveyed more than 5000 LGBT people across England, Scotland and Wales found that 10% of LGBT people experienced homophobic, biphobic and transphobic abuse or behaviour online in the last month. This number increased to one in four trans people (26 %) who experienced transphobic abuse or behaviour online in the last month. Moreover, the study found that 23% of LGBT young people aged 18 to 24 were personally targeted online in the last month, with this number rising to 34% of trans young people. The study also found that 20% of Black, Asian, Minority, Ethnic (BAME) LGBT people experienced abuse online in the last month compared to 9% of white LGBT people. Non-binary LGBT people were found to be significantly more likely than LGBT men and women to experience personal online abuse with 26% experiencing such abuse.

Additionally, a US study by the Pew Research Centre on online harassment found that 59% of black internet users said they had experienced online harassment compared with 41% of white internet users and 48% of Hispanic internet users. 38% of black internet users also said they had been called offensive names. US activist Shireen Mitchell described to Amnesty International how abuse against black people on Twitter often references animal names. She described how black people will sometimes be called ‘ape’, ‘gorilla’ or ‘monkey’ as a form of racial abuse online. Similarly, UK Politician and activist Seyi Akiwowo told Amnesty International that the abuse she experienced on Twitter and other social media platforms included racial slurs like ‘n*gger’, ‘n*ggerress’, ‘negro’, references to lynching and being hanged, as well as ‘monkey’, ‘ape’ and being told to ‘die of an STI’.

US-born and UK-based journalist Hadley Freeman, told Amnesty International that most of the abuse she experiences on Twitter is actually anti-Semitic – but that she receives misogynistic abuse on the platform as well. In addition, Jaclyn Friedman, a US writer and activist of Jewish descent, spoke to Amnesty International about a tide of anti-Semitic abuse she experienced on Twitter in November 2016. She said,

“I got numerous threats on Twitter threatening me with Zyclon B – that’s the gas they used to kill people in the gas chambers of the Holocaust.”

Rani Baker, a US writer and illustrator, told us about the abuse she experiences on Twitter as a trans woman on the platform. She said,

“People have made so many dehumanizing and humiliating assumptions about, references to, and descriptions of, my body, surgical results, sexual orientation and proclivities, general lifestyle and behaviours that it could fill a book. It’s shockingly common to see the most degrading descriptions of myself and my existence being bandied around by people trying to get under my skin.”

It is important to note that identity-based abuse can be used to target women from marginalized groups in different ways. A US sex worker and advocate who wished to remain anonymous, told Amnesty International that abuse on Twitter targeting sex workers often includes deliberately being ‘outed’ with a view to shaming or humiliating them. She explains,

“When dealing with a criminalized and stigmatized population being attacked by people who are not in that population; there is always a question of power…Twitter being an open space is a problem for targeted abuse against sex worker advocates. For me the fear of being outed means I couldn’t advocate effectively. Being outed is something I’ve seen over and over again on Twitter. People live in constant fear of being outed non-consensually…It’s really hard to do advocacy when you are waiting for the other shoe to drop”

Doxing

Abuse against women on Twitter can also include ‘doxing’ (slang for ‘docs’ or ‘documents’) which involves revealing personal or identifying documents or details about someone online without their consent. This can include personal information such as a person’s home address, real name, children’s names, phone numbers and email address. Doxing is a violation of a person’s privacy and the aim is to distress, panic and otherwise cause alarm. In the USA, Amnesty International’s online poll found that almost 1 in 3 (29%) women who experienced abuse or harassment on social media platforms had been doxed.

Former UK Politician Tasmina Ahmed Sheikh told Amnesty,

“Somebody thought it was a really good idea to tweet out my home address with post code which meant the police then had to patrol my house. It was at a point where my husband and I were out and my kids were at home on their own so it was really worrying.”

US writer and activist Jaclyn Friedman told Amnesty International about the security measures she took before she published a report about abuse on Twitter out of fear of being doxed,

“Before we launched our Twitter report, I got a new security system on my house. We lived in a really safe neighbourhood and I’d never thought about it before – but I didn’t want to go to bed at night and think ‘what if they dox me at 3am when I’m sleeping? It felt too vulnerable….

…It’s time and energy and actual money that goes into making sure that I can say to Amnesty in this interview – ‘oh sure, publish my name, publish my face’. I consistently resent that…It’s absolutely a tax on women’s speech’.”

The fear of being doxed is a particular concern for women in the USA where publishing a person’s address online can lead to ‘swatting’ – which is when someone makes a fake emergency call to trigger a large police response at the target’s home. The response often includes a heavily armed SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) team who arrive expecting a hostile situation. For example, in January 2016, US Congresswoman Katherine Clark, who is a vocal proponent of legislation against online abuse in the USA was ‘swatted’ – soon after she sponsored a bill to combat swatting.

Sharing sexual and private images without consent

Sharing sexual or private images without consent is a violation of women’s right to privacy and is usually carried out by an ex-partner with the aim of distressing, humiliating or blackmailing a woman. While a woman may have initially consented to having images taken and voluntarily shared them with an individual, she may not have given that person permission to share the images more widely. It is the non-consensual aspect of this form of abuse which makes it distinct from sexually explicit content online more broadly.

Of the women polled by IPSOS Mori for Amnesty International who experienced abuse or harassment on social media platforms, 10% in the USA and 8% in the UK said that intimate images had been posted of them online without their consent.

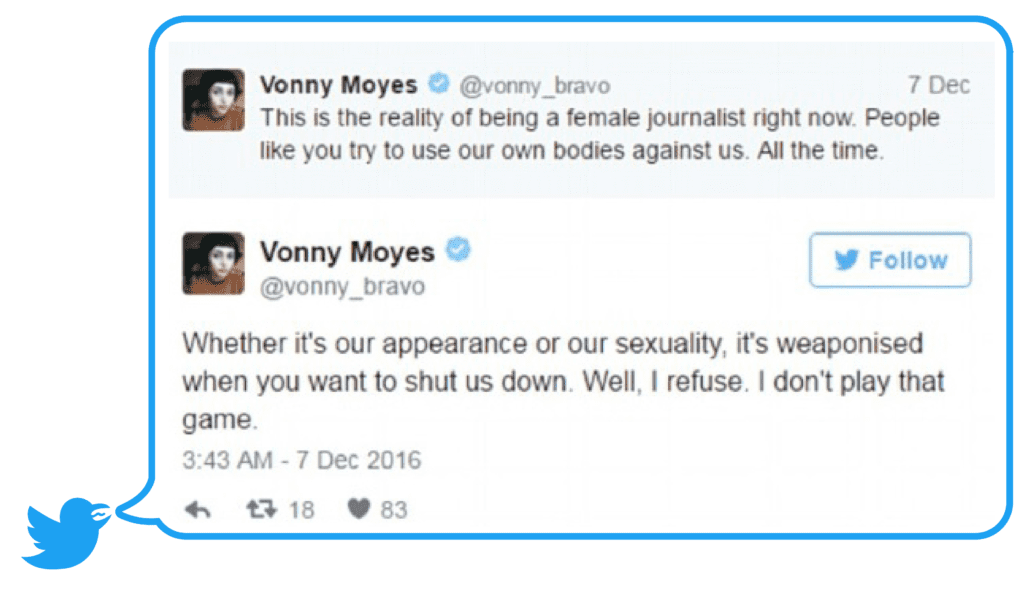

When UK journalist Vonny Moyes had private images of her shared on Twitter without her consent, she used the same platform to hold the perpetrator to account. Her response included a series of tweets that stated,

“So @*************** has just found and posted nudes of me. I would very much appreciate your help in reporting him for this.”

“The thing is @*************** – this only works as weaponry if I accept the shaming. I did not give you those or permission to look at me.”

“This is the reality of being a female journalist right now. People like you try to use our own bodies against us. All the time.”

Targeted Harassment

Targeted harassment online involves one or more people working together to repeatedly target a woman with violence or abuse over a short or coordinated period of time with the aim of humiliating her or otherwise causing distress.

Games Developer Zoe Quinn experienced what has become one of the most well-known cases of targeted harassment online. The term ‘Gamergate’ was coined in 2014 following a relentless flood of online violence and abuse that she and other prominent women in the gaming industry were subjected to on multiple social media platforms, including Twitter. The extensive violence and abuse targeting Zoe began after her ex-partner posted an article about their relationship and accused her of an affair. The post was picked up on platforms like Reddit and 4Chan and resulted in a barrage of violence, abuse and harassment against her.

The very nature of the Internet allows content posted on social media platforms to ‘go viral’ and be shared across platforms almost instantly – which means that violent and abusive content can be easy to share or repeat and difficult to contain. One abusive or violent tweet against an individual, for example, can quickly multiply into hundreds or thousands of abusive or violent tweets against that individual within minutes.

UK actor and poet Travis Alabanza told Amnesty International about the targeted harassment they experienced in November 2017 after a tweet they posted went viral. Travis recounted,

“I tweeted before I went to bed and woke up and was like ‘why do I have 70O+ notifications on Twitter? A few days later Twitter sent me a tweet saying ‘Congratulations your tweet is featured in the Moments!’…I’m used to Twitter traffic but something felt a bit different about this. We’re talking, I think 100 tweets per minute. There were points where you could scroll my name and you could scroll 7 or 8 times and you’d only be 3 minutes in…

…I remember just looking at the abuse and being so shocked and just sitting there and my friends being like ‘What do you need?’ and me just saying ‘I don’t know.’… A lot of the abuse was to die and much of it said ‘You’re a man’. They also took photos of me and then circled parts of my face that are ‘manly’.”

Many women we spoke to emphasized that the sheer volume of violent and abusive tweets they receive on Twitter is specifically what they find so overwhelming about the platform.

US writer and presenter Sally Kohn explained,

“The abuse on Twitter is sort of constant. And it’s disturbing when you recognize that is so kind of constant and normalized that you don’t even notice it anymore…I can’t find the reasonable stuff amongst the trolls, I really can’t.”

When UK Shadow Home Minister Diane Abbott told Amnesty International about the difference between offline abuse she received when she first became a Member of Parliament, and the abuse she receives on social media platforms 30 years later, she stated,

“It’s the volume of it which makes it so debilitating, so corrosive, and so upsetting. It’s the sheer volume. And the sheer level of hatred that people are showing.”