What do we mean by racial justice?

When it comes to human rights, racial justice work means going beyond preventing individual cases of racial discrimination and combating structural oppression. It involves working towards systemic change and solutions, by targeting the root causes of racial oppression as it intersects with patriarchy, colonialism and slavery as well as economic inequality.

At the heart of this work lies the voices of people subjected to racial injustice and their experiences of human rights violations due to systemic racism.

What is systemic racism?

Systemic racism can be defined as policies and practices that exist throughout a whole society that leads to a continued unfair advantage to some people and unfair or harmful treatment of others based on race.

Systemic racism takes many forms including:

- When one group of people and their values, ways of doing things are classified as “normal” and other groups of people are “abnormal”.

- The political power to withhold basic rights from people of colour and use the full power of the state to enforce segregation and inequality, in practice.

- The social power to deny people of colour full inclusion or membership in associational life.

- The economic power that privileges white people in terms of job placement, advancement, wealth, and property accumulation.

How does racial discrimination impact society?

In international law, “racial discrimination” is understood as “any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life”.

It can include Black people and other racialised communities. It can intersect with religious and ethnic minorities and can take specific forms when targeting people on the move. There are numerous ways in which racial discrimination affects societies and people’s lives.

Policing and the criminal justice system

Globally, the police system is blighted by racial and discriminatory practices. People that are disproportionately affected by these practices include Black people, as well as Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims and other racially marginalized communities.

They are subjected to racial profiling, unlawful arrests, cruel, degrading, and inhumane treatment as well as police violence that can result in death. They also face increased identity checks, arrests, incarceration for drug-related offences, petty offences and “public order” offences, as well as migration-related offences and the criminalisation of sex work.

For example, during the Covid-19 pandemic, the enforcement of lockdown measures had a disproportionate impact on racially marginalized individuals and groups. In Brazil, the “war on drugs” has been used to justify unnecessary and excessive use of force, including extrajudicial executions. As a result, thousands of afro-Brazilians living in favelas have died.

Migrants, refugees and asylum seekers

There has been an alarming trend of systemic racial discrimination, including violence, against migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. This callous treatment in some circumstances has amounted to crimes under international law – disproportionately affecting Black migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

In Tunisia, racist remarks by the President ignited a wave of anti-Black violence in the country, including violent attacks against Black migrants and students, which were downplayed by Tunisian authorities.

In Qatar, migrant workers – especially from Africa and South Asia – face discrimination because of their national origin and race in several areas, including salaries.

In Europe, migrants, refugees and asylum seekers are increasingly forced to resort to unsafe routes to access European borders due to ongoing efforts to block safe and legal routes by European policymakers through pushbacks and the criminalization of rescue assistance.

Access to healthcare

Due to structural inequalities, racism creates barriers that stop some people from getting quality healthcare, which can exacerbate health issues further down the line. Often, these barriers are the result of not only a person or group’s race, but also a combination of other factors, such as gender, sexuality, income, citizenship, employment status, and the presence of a health condition or disability.

The issue is widespread. For example, in Namibia, the San people face significant barriers to access healthcare due to their remote location. Although most rural Namibians face similar distance-related barriers to accessing healthcare facilities, the San’s multiple challenges including lack of education, financial means and poor access to public transport makes it even more difficult to access healthcare facilities, which in some cases are 80kms away.

Access to education

Children experiencing racism have been prevented from accessing quality education.

For example, Romani children have suffered systemic and ongoing discrimination in primary education in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and other European countries for decades.

These human rights violations are systemic in nature and as a result, Romani children have been placed into special schools and classes intended for pupils with mental disabilities, they have been segregated in Roma-only schools and classes, and they have been treated differently and with prejudice in mainstream schools, simply because of their ethnicity.

Racial and climate justice

Sadly, ethnicity, race, class, and caste go hand in hand with the detrimental effects of climate change and fossil fuel-related inequalities.

In India and Nepal, women and girls belonging to so called “low castes” such as Dalit, are more susceptible to the negative impacts of climate change as they are forced to live in segregated and isolated housing. Time and again, these women are ignored and overlooked in humanitarian and rehabilitation responses and are persistently deprived of resources and opportunities to influence decisions concerning them.

In North America, air pollution disproportionately affects poorer racialized communities especially Black communities, whose neighbourhoods are more likely to be situated next to power plants, refineries, and highways. This leads to higher rates of respiratory illnesses and cancers, and Black people are three times more likely to die of airborne pollution than the overall US population.

It also has a detrimental effect on Indigenous Peoples. The burning of fossil fuels is killing people and damaging the environment. But as the global economy starts to move away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy sources, it can also harm people’s human rights, as well as the environment, as it relies upon a massive increase in the mining of metals and minerals. If mining companies and their buyers continue these practices, they could deepen the human rights abuses experienced by front line communities, including Indigenous Peoples and block the path to a sustainable future.

Crimes against humanity and international justice

Amnesty International is concerned about the double standards when it comes to international justice, including the apparent failures of the International Criminal Court (ICC) to hold suspected perpetrators from powerful states to account and to ensure equal access to justice for all victims of crimes under international law.

Recent decisions by the Office of The Prosecutor of the ICC not to investigate or to deprioritise investigations into crimes allegedly committed by nationals of powerful states, such as the US and the UK, appear to beg the question of whether the principles of international justice are applied equally to all perpetrators, regardless of how powerful they are. Similarly, the voluntary funding allocated to the investigation in Ukraine as compared to the budgetary constraints on investigations into the other situations such as Nigeria and Afghanistan risks perceptions of a hierarchical system of international justice in which victims of crimes under international law do not enjoy equal access to justice.

Moreover, there has been a lack of progress in the ICC’s investigation into the crimes committed in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. These crimes include apartheid, which is a crime against humanity. Apartheid is a system of prolonged and cruel discriminatory treatment by one racial group of members of another with the intention to control the second racial group.

Case Study: Israel’s Apartheid against Palestinians

Since the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, successive governments have created and maintained a system of laws, policies, and practices designed to oppress and dominate Palestinians. This system plays out in different ways across the different areas where Israel exercises control over Palestinians’ rights, but the intent is always the same: to privilege Jewish Israelis at the expense of Palestinians. This is apartheid.

Israeli authorities have used four main strategies to maintain the system of apartheid:

- They separate Palestinians from one another into distinct territorial, legal, and administrative domains, and deny them their right to return

- They seize Palestinians’ land and properties, deny building permits, demolish houses, and forcibly evict Palestinians from their homes.

- They segregate Palestinians into enclaves, based on their residency and legal status.

- They deny Palestinians economic and social rights, including through discriminatory allocation of resources.

Mohammed Al-Rajabi, a resident of Silwan in occupied East Jerusalem, whose home was demolished by Israeli authorities on 23 June 2020 on the basis that it was built “illegally”, described to Amnesty International the devastating impact on his family:

“My plan was for them to have a warm family home close to their loved ones and family members. Now I’m passing on the memories of their first childhood home being destroyed.”

My plan was for them to have a warm family home close to their loved ones and family members. Now I’m passing on the memories of their first childhood home being destroyed.

Mohammed Al-Rajabi

Movements for racial justice

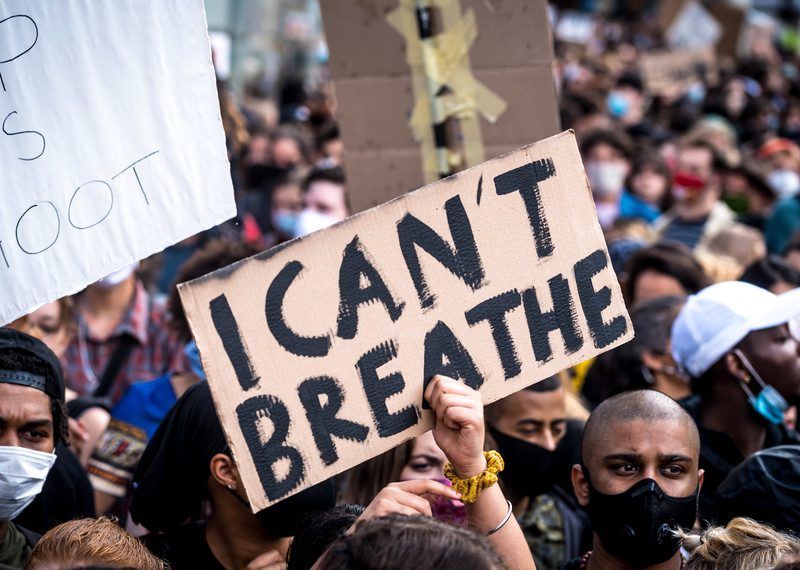

For decades, the racial justice movement has been accelerating, with people bravely speaking out in the face of injustice around the world.

In recent years, #BlackLivesMatter has been at the forefront of change. Founded in 2013 in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer, Black Lives Matter fights to eradicate white supremacy and build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes.

However, speaking out is not easy, especially if you are a minority.

The ability to protest safely is an issue that intersects with the right to be free from discrimination. People who face inequality and discrimination, based on their age, race, gender identity and many other factors, face even more dangers to their right to protest.

It is crucial that everyone can protest safely and without discrimination – an issue Amnesty International is tackling through its Protect the Protest campaign.

Case Study: Ban the Scan

Around the world, law enforcement agencies are using facial recognition technologies to stifle protest and harass minority communities. These systems violate the right to privacy, threaten the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and expression, and to equality and non-discrimination.

How does it work? Well, tech companies develop facial recognition technology by scraping millions of images from social media profiles and other databases such as driver’s license registries, without our knowledge and consent. Facial recognition technology can amplify racially discriminatory policing and threatens the right to protest. It mostly impacts Black and minority communities, as they are at an increased risk of being misidentified and falsely arrested – in some instances, facial recognition has been 95% inaccurate.

Without action, facial recognition technology and its dangerous effects, are going to become a normal part of life and minority groups are going to be continually targeted and harassed.

That is why Amnesty International launched a campaign, focusing on the USA, Hyderabad and OPT, calling to Ban the Scan.

What is Amnesty doing to fight for racial justice?

Amnesty International is calling for people who have been historically and systemically discriminated against to enjoy equality in law and practice.

States must ensure justice and redress including through the removal of racist laws, policies and practices, and guarantee equality in access to economic and social rights. They should also take measures to end the over-policing and overcriminalisation of discriminated people and communities.

To learn more about descent-based discrimination and how to tackle it, take part in our course, Decoding Descent Based Discrimination.